For Mr. Nguyen Thanh Quang – Chairman of the Board of Directors of Indochina Industrial Investment and Export-Import Corporation (HNX: DDG), carbon credits are like many other certificates, all aimed at reducing emissions, carbon neutrality, and moving towards the global Net Zero goal.

Emission reduction is one of the top priorities for many countries around the world today. In Vietnam, this issue has heated up since the Government committed to the “Net Zero” or “carbon neutrality” goal by 2050, while also setting a trial market trading roadmap for 2025, officially operational by 2027.

The term “carbon credit” has been appearing frequently in the media for many years. It can even be seen as a potential commodity, as Tesla made substantial profits in 2020 not from selling electric cars but from selling credits, or recently Vietnam announced the successful sale of 10.3 million credits through the World Bank, earning about 1.2 trillion dong.

Carbon credits have not been around for long, so public understanding of this concept is sometimes vague. Recently, the writer had the opportunity to converse with Mr. Nguyen Thanh Quang – Chairman of the Board of Directors of Indochina Industrial Investment and Export-Import Corporation (HNX: DDG).

A businessman from Quang Ngai province, with an engineering background, a Ph.D. in thermal engineering, who was a research fellow at the Dresden University of Technology, Germany, and is currently a lecturer at the Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology. He shared practical, insightful yet understandable insights about carbon credits, how the credit market operates, and the ultimate goal of this issue.

What are the Carbon credits?

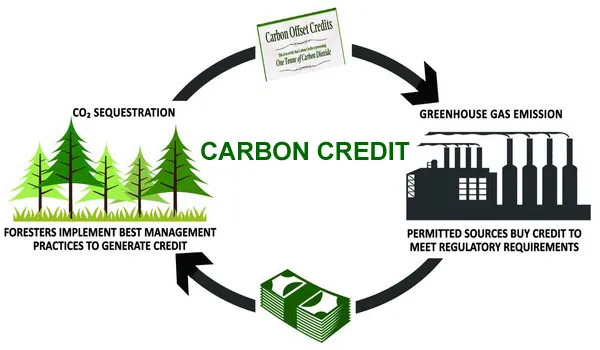

Carbon credits (or CC) are simply understood as 1 ton of CO2 gas (or other greenhouse gases like CH4, NO2… converted into CO2 units) certified for commercial trading. It represents the “right” to emit CO2 by a unit, enterprise, or organization and must be confirmed by a reputable, legal organization.

“For example, a company in a sector emits CO2, such as a thermal power plant using fossil fuels. In the current and upcoming context, that emission must be certified,” Mr. Quang emphasized.

“It is necessary to know that carbon credits are the ‘right’ to emit CO2 into the environment,” Mr. Quang stressed. In other words, carbon credits are essentially a type of right. The difference between credits lies in the emission source. Thus, the world has the additional concept of “carbon certificates,” which are certificates of greenhouse gas emission reduction or absorption, certified by authorized organizations.

These certificates will produce different credits (essentially still 1 ton of CO2). For example, carbon credits under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), credits through I-REC (renewable energy certificates), or carbon sequestration credits…

According to Mr. Quang, there are other types of green certificates in the world, such as ISO 14064-1 carbon certificates, energy-saving certificates, smart transportation certificates, electric vehicle conversion certificates, emission-producing carbon capture certificates, green building certificates, agricultural certificates… Despite different emission sources, all aim “to reduce CO2 emissions, mitigate greenhouse effects, mitigate climate change to move towards the Net Zero goal,” quoting the DDG Chairman.

Basically, a company can obtain carbon credits if it controls emissions below the quota or when it has achieved carbon neutrality. Mr. Quang explained that instead of using fossil fuels, a plant can switch to using biofuels or biomass. These are fuels that, when burned, emit CO2 but are already carbon-neutral.

Another solution is to plant forests to reduce CO2 levels. “Projects for CO2 recovery through tree planting will be established. The planted area will be monitored, confirmed, and measured for CO2 recovery, and carbon credits for forest planting will be issued and tradable,” Mr. Quang shared.

Regarding forest planting, Mr. Quang assessed it as more sustainable, with lower investment value compared to machinery and equipment. However, the drawback is the need for very large areas, up to tens of thousands of hectares; therefore, there will be many procedures related to project direction and government licensing. “Only countries and regions with abundant land can implement this plan,” Mr. Quang said.

Some countries have solutions to carbonize CO2 and then bury it underground or retrieve CO2 and compress it, push it deep into the ocean. Thermal power plants can burn both biomass and switch to green fuels such as hydro or green ammonia.

In general, to obtain carbon credits, it must be demonstrated that CO2 emissions into the environment have been reduced compared to the quota. Carbon credits will be issued based on the amount of CO2 that companies can “save”.

With the goal of reducing CO2 emissions, governments and government alliances also impose mandatory emission regulations, forming carbon credit markets. Mr. Quang stated that the world currently has two markets, namely the “mandatory” and “voluntary” markets.

Mandatory markets are when countries, organizations, or companies must commit to complying with climate change mechanisms and decrees such as the Kyoto Protocol, COP24, COP26… This forms the mandatory market.

“In the mandatory market, countries must inventory and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Nations must commit to how much CO2 emissions they will emit, then allocate them to enterprises. Enterprises exceeding the quota must find ways to reduce emissions or purchase credits from units that have reduced emissions and been issued credits,” Mr. Quang quoted.

For example, if a company exceeds the quota (emits net positive emissions), it must purchase credits, which will basically increase costs and reduce competitive advantages when facing companies that have operated in an environmentally friendly manner. Therefore, for sustainable development, companies must find ways to reduce emissions to serve the common goal of carbon neutrality.

On the other hand, some companies are not necessarily required to participate in the mandatory market because they may already be carbon neutral. These companies will participate in the voluntary market if they have surplus CO2 emissions rights (or negative net emissions).

In the trading market, buyers are companies with positive CO2 emissions, which can be steel manufacturers, cement producers, petroleum refineries, chemical manufacturers, textile producers… Sellers are any organizations with overall negative net CO2 emissions, such as forest planting project implementers, renewable energy development companies, electric vehicle manufacturers…

There are also intermediary companies. These are units that connect buyers and sellers, perform certification procedures for buying and selling, and enjoy commissions. They can also directly purchase from companies with selling needs and then sell to buyers at a profit.

The difference between these two markets basically lies in the price. In the mandatory market, each credit has a relatively high price, which can be up to $40/credit or more, depending on the time. In contrast, in the voluntary market, the selling price falls to around $5/credit.

Mr. Quang explained this difference: “In the voluntary market, people can plant forests to reduce CO2, leading to lower costs and selling prices. Secondly, companies not only sell to those in need but can also sell through intermediaries, such as the World Bank, government organizations… Intermediaries will buy cheaply and sell at a higher price, earning the difference.”

“Companies that create voluntary credits feel that selling at such a price is appropriate. Buyers in the mandatory market have to spend more money. Or they have to invest a large amount to reduce emissions or have to spend a large amount to buy credits,” Mr. Quang shared.

The DDG Chairman believes that Vietnam is currently not a unit required to participate in the market. However, with mechanisms issued worldwide such as the EU’s CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism), which will be fully implemented by 2026, affecting import-export enterprises will still occur.

“There are currently 4 significant export industries to the EU, namely aluminum, steel, cement, and fertilizer. The impact of CBAM reduces the value by 4% and the output by 0.8% for steel; reduces the value by 4% and the output by 0.4% for aluminum, while cement and fertilizer are negligible. This increases pressure on business production,” according to Mr. Quang.

Therefore, even though it is not mandatory, the story of emissions reduction in Vietnam has been and is being implemented. This is evidenced by renewable energy projects (solar power, wind power, biomass, waste-to-energy…) in the Central region or the Mekong Delta; green agriculture projects (reducing fertilizers, pesticides, water, applying technology to increase efficiency and reduce waste) such as sustainable development projects in the Mekong Delta; projects replacing gasoline and diesel vehicles with electric vehicles; improving equipment efficiency to reduce consumption, thereby reducing the amount of fuel used to generate electricity and moving towards reducing CO2 emissions.

Recently, a notable project is forest planting in the North Central region. In 2023, this sector successfully sold 10.3 million forest carbon credits, earning $51.5 million from the World Bank (equivalent to a price of $5/credit).

As mentioned, there are businesses that do not need to participate in the mandatory carbon market. DDG, chaired by Nguyen Thanh Quang, is one such enterprise. Operating primarily in steam and thermal power, DDG’s areas and projects related to waste treatment, waste-to-energy, and steam supply… All are carbon neutral.

“Dong Duong does not have a carbon emission quota, so it does not participate in the mandatory market. In terms of specificity, we provide emission reduction solutions for other businesses. From here, carbon credits and credits can be obtained through the voluntary market,” according to Mr. Quang.

Taking the example of the beer husk drying plant in Ba Ria – Vung Tau of DDG, which the writer had the opportunity to visit. The plant is carbon neutral when using biomass fuel (wood chips, sawdust, rice husk, cashew shells…), considered as renewable fuel. When burned, although CO2 is emitted, it is neutralized.

The image of white smoke columns from the husk drying plant, the Deputy Director of the plant here said, the white smoke color ensures emissions meet standards, just a different smoke color and the plant will be inspected immediately.

“In the past, partners had to use fossil fuels such as DO oil to generate steam for the beer production process. DDG’s plant, on one hand, uses biomass fuel to supply steam, reducing the normal carbon emissions of the partner, and on the other hand, utilizing the heat for husk drying. Fresh husk is originally used as animal feed, but only for a short time, emitting a very unpleasant odor. After drying, husk can be stored longer, providing revenue for DDG,” the DDG Chairman said.

In addition, DDG’s plant supplements the project “CO2 Recovery and Liquefaction from Boiler Exhaust”, started in 2020 and is now operational. This system recovers CO2 from biomass boiler exhaust, collects it, and uses it in industries (welding, food, dry ice production…). From another perspective, by utilizing the generated CO2 (from sources already neutralized), it also saves CO2 that would otherwise be produced to serve other industries, thereby reducing CO2 emissions into the environment.

The current project is designed to recover 80 tons of CO2/day, running experiments at 1/3 capacity for nearly a year. Mr. Quang said, there will be similar systems in the near future, increasing the total capacity to 160 tons/day. Recently, there have been two investment funds from Japan and Malaysia interested in the project, with a planned capital mobilization of $10 – 20 million.

DDG’s leadership said that selling liquefied CO2 currently contributes about 10% to DDG’s revenue, and if the capacity is increased, the contribution could reach 30%.

The DDG Chairman also does not hide the ambition to join the voluntary carbon credit market. He said that not only the husk drying plant, DDG also has projects to produce electricity from waste or in collaboration with large CO2 emitting companies to reduce emissions. All have the potential to earn carbon credits.

“DDG aims for credits under mechanisms such as CDM – fuel switching, I-REC – through small-scale power plants using waste or biomass, and carbon storage credits. In this market, the potential customer group for DDG includes steel, oil refining, cement, paper, glass, fertilizer, energy… industries,” Mr. Quang said.

However, Mr. Quang also believes that there is still much to prepare, as well as difficulties in joining the voluntary market. “We will have to understand the mechanisms, methods to obtain carbon certificates from reputable organizations worldwide, and then proceed with the certificate issuance process. In general, it is costly, both in terms of time and money, and requires consulting firms,” he said.

Experience of students at DDG

Master Nguyen Thi Kim Phung – Deputy Director of the Enrollment and Business Relations Center of the University of Finance – Marketing shared during the student visit to DDG’s Heineken beer husk drying plant in Ba Ria – Vung Tau: “DDG is one of the large and closely related import-export manufacturing units to fields and industries of the university. Import-export means DDG is also connected with other countries, so students coming here will learn a lot and have opportunities for development related to their future careers.

The orientation of the university is that students must meet full knowledge, skills, and attitudes for each profession upon graduation. I see that at DDG, most plants are highly automated. The number of employees serving the plant is therefore not large. So, students must realize that the competition for labor is very high when technology is operational, requiring high-quality human resources.”

Souce: Chau An (Vietstock)

Originally posted 2024-03-26 08:37:52.